What does privacy mean today?

While we tick, click, swipe, type, and press ok-all-the-way through any number of the various applications and services we try, buy and use throughout the course of a day, one may not often stop to reconsider the repercussions of such a ‘why-worry’ lifestyle.

Furthermore, without a good, truthful perspective of what we’re really giving away while we’re doing this, one may even be left feeling like they shouldn’t need to care.

I mean, when we’ve got mainstream moguls[1] saying they value our privacy first and foremost, and then ‘bake’ that into everything they do, why worry? And about what? And maybe that’s partly where this Neuman-esque ideology starts. The other part of it is something I’ll call the “assumption of transparency.”

The assumption of transparency is the belief that WYSIWYG, and that because X values Y, that Z will too.

The assumption of transparency:

WYSIWYG = What you see is what you get. (EG, no gimmicks or hidden agendas)

Y is your data, and X is the guy promising they care about Y’s privacy.

X wants your data big-time. X promises to use it only to make the services you use better, and so far it’s been working out.

Now enter Z, an app developer that also has access to that same data. Z might care about privacy and security, but we won’t know that for sure.

How many of us have apps we do not use on our phones? This is by far the biggest offender; the mobile operating systems we use and the apps therein, where we keep said applications pretty much “forever”– even after we’ve long stopped using them.

Context

Have you ever let the recycle bin on your computer get really, really full, and then when you finally went to empty, it took so long that maybe you stopped doing that?

Did you maybe start emptying the trash a little more often afterwards? I know I did. For some of us, that may not actually be a relevant example any longer, but for those of use who’ve been around long enough to watch a status bar made of blue blocks slowly work its way across the 16-bit screen, we started emptying the trash a bit more frequently. It became a habit, or a practice.

Circling back, what about those apps on your phone? Do you regularly remove the apps you don’t use? Probably not. If you’re like I was, the answer might even be “Why?” – followed up sharply by “I might use that one day! Besides, it’s not like it’s slowing the device down by much, anyways.” Plus, there are features like ‘Offload Unused Apps’. So what’s the point?

Let’s take this one step further.

How many of us have activated something, like a free app or service, and then stopped using it after we decided we didn’t care too much for it? Probably a lot. Did you offload that unused app? Maybe, maybe not. Most of us have deleted an app that we stopped using. But did you also you go back and remove the token you used to sign into that site or service after you stopped using it?

The assumption of security:

A. When initially signing into this service, regardless of how, it is assumed relevant and acceptable security controls are present, whether or not that is actually true. This includes signing in via something called Attribute Release. (Think of those buttons ‘Sign in with Facebook’, and remember this term.)

B. When ceasing to use the service, it was assumed that any data or credential therein would be protected by said app or service, or by the service used to sign in via Attribute Release. (I signed in with Facebook so it is secure by their standards, right?).

C. If left alone, it was assumed the account would eventually be closed for inactivity / just simply fall to disuse. Either way, the account is safe.

D. Nothing would change.

Reality

For me, the first round of emails came from the Last.FM incident[2] dating all the way back to 2012. We then saw that same report expanded to cover several other major services, followed still by several other breaches over the years.

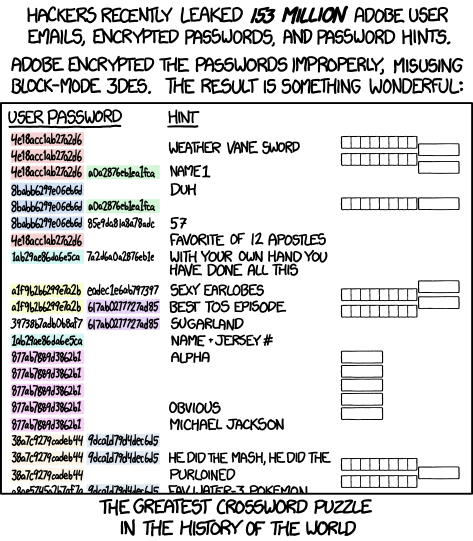

In the industry, we also started to notice a pattern, like reference algorithms[3] being used in several implementations across different vendors, yielding incredible (and ignored) risks to the users of those services.[4][5] Or completely ignored security controls altogether. A problem that truly goes both ways it seems.

There were other patterns too– like app developers making interesting or even outlandish permissions required for apps that looked like they really shouldn’t need capabilities like that. And there was growth. How quickly we went from simple drive-by “droppers” and cookie grabbers[6] and coin miners[7][8][9] to armored, polymorphic, av-evasive, memory-resident everything, along with signed malware in the form of updates introduced in applications we thought we could trust[10][11].

We started seeing more and more breaches[12], to the point we adopted a new outlook, as Katherine Kearns tells us: “Companies have done a lot of things right, but it is not a matter of if but when they will come under attack.”

Perhaps some wisen up after that first email regarding a breach their data may have been a part of– complete with a half-a-password and some asterisks denoting that yep, they gotcha. This is also assuming that the person even cares.

Because privacy doesn’t really matter if you don’t care about it.

Due Care

“Due care” is actually an industry term, and it matters enough to cause legal issues if you don’t consider it in a professional setting. But as for the folks not subject to this, who aren’t required to care, they actually won’t. (Why worry?).

It can take time to grasp this. Some may attend awareness courses at work, or even independently. Still others get their first sense of caring about privacy from services like haveibeenpwned.com[13] or LifeLock[14].

For the ones that finally get it, suddenly things are different. You care. It is only when someone takes control of caring about privacy that they will begin to move towards protecting it. Some of us can learn this lesson without receiving an email first, but we’ll talk about that in a bit.

Data Points

When we talk about privacy, we’re really talking about data points. Some of them are readily available via public records, or one of those handy little people-search tools. Others are made available by your own devices, or via your social media presence.

Still others come from a wide range of data collection sources, and there are even tools designed to filter and correlate this stuff. Some points get anonymized and lost to the lake, others stay very much tied to a device and user account forever (like a supercookie)[15]. Comments and Likes end up somewhere in there, too. The collection of these data points make up something we call the ‘digital footprint’. To recognize and respond to this, we can adopt an ideology that ‘it is never really deleted’[16] and consider this heavily before introducing content to the web, or signing up for an app or service.

When we give up our privacy, we allow the various points of data being collected about us to be used in any manor suited to the engineer in control of that data. While I can’t speak on the use cases, I can speak on some of the many[17], many counts of misuse[18] recently aired by the biggest of names, with allegations tied to things as serious as the Presidential Election[19] itself. Then, there is also the fear of data ‘weaponization’[20] that may be partly responsible for leading some users[21] toward flat out deleting their accounts.

Privacy as a practice, whereas we employ countless considerations towards protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the data we transact, fails when the data meant to be protected falls into the wrong hands, or is used outside of intended purposes. (They used our data for WHAT?!)

Sadly today, this is becoming more of an unknown unknown. We don’t know what kind of data is being collected, for what purpose or by whom. If we don’t know what will ultimately happen to the data being collected about us, then what is the answer? Perhaps the answer is less. In terms of apps and privacy, does less really mean more? Maybe.

Security sort of does this in reverse, whereas more security means less functionality. Close, but no cigar. Lets instead look at it terms of trust. Trust vs Privacy. In this respect, less starts meaning more by default. Less trust inherently means more privacy.

When we stop trusting things by default, and we remove the assumption of transparency; When we stop assuming that the developer has the best intention; that they implemented the security properly; and we stop assuming that things won’t change, we take control. I believe the adage goes something like ‘Hope for the best, brace for the worst.’

Digital Hygeine

So what can we do about an overflowing bin? We can empty it, sure. We could also consider the analogy as it pertains to our digital footprint, and approach it with a sense of “spring cleaning”, only this version is more of a rolling release. We can regularly review the apps we solicit attribute release to, remove them if necessary, and remove tokens we no longer use along with any related session cookies. Almost sounds like there could be an app for that.

One sure-fire way that I’ve found to regulate the number of authenticated sessions and services I use as a whole is to search out any “Welcome to _____” emails into a list and review it to see if there is anything I might need to address, like a service I logged into but know for sure I won’t use again, or to see how I signed up in the first place.

Touching back on the X, Y, Z equation:

If Z discovers how lucrative it is to sell data points, what stops them from introducing an update that requires more than just access to your Contacts? Will you allow it, knowing you’ve used the app and may have even developed a bit of “trust” for it? Would you be savvy on what was happening?

What if Z sells the data? Or worse, what if Z doesn’t know how to properly implement security controls, and while Z does their best, there is still a breach and that data gets exposed? What if this is compounded by attribute release, whereas you signed in with a major service and now that credential is possibly compromised?

Would you know before it’s too late and something malicious was done? We’ve got disclosure timelines and diligence initiatives, and still we have the glaring examples like Last.FM. We didn’t even learn about the true scope of all of that until 2016. That is an awful long time to be in the dark.

Conclusion

With some considerations, we can introduce healthy privacy practices in the same way we [try to] establish positive moral values, and with that we can educate both users and youths to the benefits of healthy practices and the pitfalls of unhealthy ones.

A person must value privacy before they will move to protect it. In an age where folks adopt phrases like “why worry when I’ve got nothing to hide?” it may seem they don’t quite grasp the idea of “something to lose.”

So what does privacy mean today? A lot more than it did 20 years ago. Today, privacy means digital hygiene, regularly cleaning out the cookie jar, and limiting exposure.

By now we’ve [hopefully] learned a few lessons, cleaned out some old session cookies and shortened a list of authentication tokens down to a known state. This doesn’t stop data collection, but it is a healthy start towards taking control of what you give away.

-Shane

Link to original article.

References:

[1] https://www.apple.com/privacy/features/

[2] https://techcrunch.com/2016/09/01/43-million-passwords-hacked-in-last-fm-breach/

[3] https://blogs.dxc.technology/2016/07/07/windows-10-secure-boot-and-the-system-management-mode-smm-bios-vulnerability/

[4] https://support.lenovo.com/gb/en/solutions/LEN-8324

[5] https://uefi.org/sites/default/files/resources/UEFI_Plugfest_May_2015%20Firmware%20-%20Securing%20SMM.pdf

[6] http://breakthesecurity.cysecurity.org/2011/09/how-to-create-cookie-stealer-coding-in-php-get-via-email.html

[7] https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2018/03/theres-a-currency-miner-in-the-mac-app-store-and-apple-seems-ok-with-it/

[8] https://www.techworm.net/2019/02/microsoft-windows-app-store-mining-cryptocurrencies.html

[9] https://www.mobileappdaily.com/google-bans-crypto-apps-from-play-store

[10] https://bgr.com/2019/10/26/iphone-apps-malware-found-in-app-store/

[11] https://www.thegeeksclub.com/list-android-malware-apps/

[12] https://digitalguardian.com/blog/history-data-breaches

[13] https://www.haveibeenpwned.com

[14] https://www.lifelock.com

[15] https://mashable.com/2011/09/02/supercookies-internet-privacy/

[16] https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/15/18226785/twitter-deleted-dms-stored-years

[17] https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/10/facebook-cambridge-analytica-a-timeline-of-the-data-hijacking-scandal.html

[18] https://www.forbes.com/sites/zakdoffman/2019/03/16/facebook-accused-of-cambridge-analytica-cover-up-as-criminal-prosecutors-investigate/#7c14176c4f0d

[19] https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/03/facebook-haunted-by-its-handling-of-2016-election-meddling.html

[20] https://www.democracynow.org/2020/1/10/defense_contractors_are_using_a_new

[21] https://www.nbcnews.com/nightly-news/video/delete-facebook-movement-grows-amid-brewing-backlash-1194335299785